Decoding the Connection: Depression and Alzheimer's Explained

Over 7 million individuals in the U.S. are affected by Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia (ADRD). While certain risk factors, such as genetic predisposition, cannot be altered, several others may be addressed. Depression, referred to medically as major depressive disorder (MDD), is one of the most common contributors. It affects between 11.1% and 14.7%. ADRD cases —impacting approximately 1 million people in the U.S.—are linked to MDD.

Subscribe to our newsletter For the most recent science and technology news developments.

Currently, scientists from the UConn Center on Aging have identified several processes connected to these issues, offering those who are vulnerable and medical professionals more insight into how the illness could potentially be avoided or reduced.

For many years, we have understood that depression is among the most significant, possibly avoidable risks for developing Alzheimer's disease," states Breno Diniz, MD, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at UConn Health and the Center on Aging, whose professional work has centered around addressing this challenge. "Yet, we remained unclear about the underlying reasons.

Diniz's latest research, published in the journal Nature Mental Health has identified two important elements connecting these conditions: proteostasis, which refers to how the body produces and processes proteins; and imbalance in immune reactions.

Disease depression surpasses mere sadness," Diniz states. "Its effects can be quiet, potentially emerging long after.

The strength found in proteins

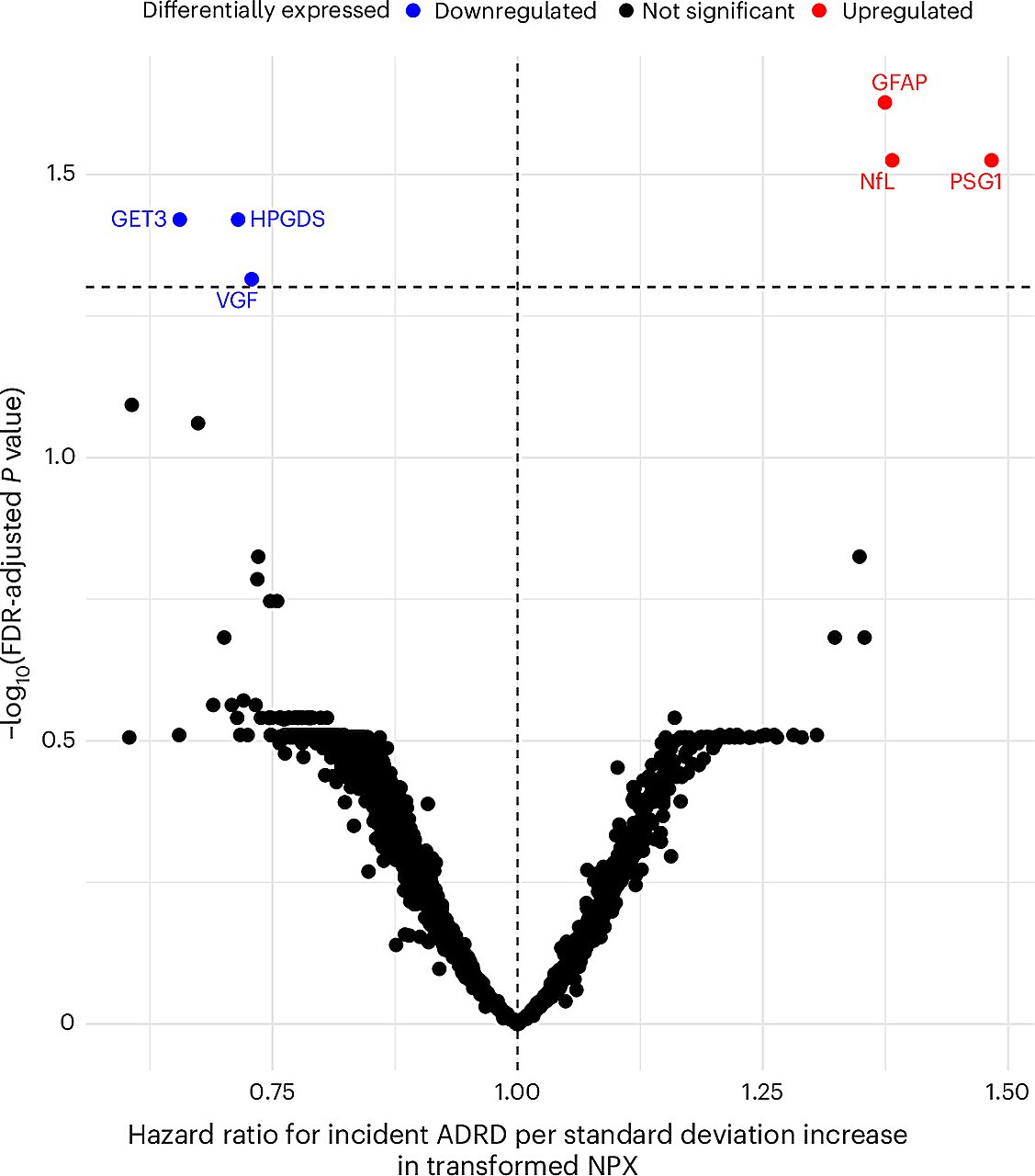

The study conducted by Diniz's group discovered several protein indicators within the body that appeared to elevate the likelihood of developing ADRD across all individuals—those with and without prior experience of MDD. These indicators are connected to broad physiological mechanisms that typically evolve over time, including inflammation, cellular replication, and apoptosis (the process through which harmful cells are destroyed and eliminated from the system).

However, among individuals with major depressive disorder, the researchers observed a distinct alteration in the mechanism of protein homeostasis. This modification led to heightened inflammation in the brain, thereby elevating the likelihood of progressing toward ADRD.

This is a causal relationship," notes Diniz, adding that these two elements—alterations in proteostasis and heightened neuroinflammation—"appear to interact, working in tandem to raise the likelihood of developing dementia.

With this understanding, the research group created a Proteomic Risk Score designed to evaluate the likelihood of an individual with depression progressing to ADRD. This innovative method examines various proteins and provides "a clearer approach to assessing dementia risk in such patients," according to Diniz.

To the researchers' astonishment, the recently created tool proved to be a superior indicator of ADRD risk compared to earlier models. It outperformed models that assess traditional risk factors for ADRD, not only in the broader population but also in individuals experiencing depression—offering optimism for early identification and intervention.

That's an extremely strong model," notes Diniz, "with clear medical uses.

The Proteomic Risk Score system will assist doctors and individuals in thoroughly assessing their risk factors for ADRD, and could also aid scientists in more effectively choosing participants for studies focused on preventing or intervening in ADRD.

Breaking it down

This research involved Diniz and his colleagues who employed both proteomic and genetic methods to examine information from the UK Biobank, focusing on ADRD developments in midlife individuals experiencing depressive symptoms.

The field of proteomics involves examining the proteins generated by cells within the body. Genomics, which focuses on an individual's complete genetic material, naturally pairs with proteomics because DNA dictates the types of proteins synthesized by cells. When these two methods are integrated, it is referred to as proteogenomics, offering scientists a more comprehensive understanding of intricate biological mechanisms and their connections to various diseases.

"Each molecular level — from genes to epigenetics, RNA, and proteins — provides distinct biological data and may play varied functions in ... developing predictive models," says Diniz. "Combining these elements enhances the strength of the models, moving them nearer to achieving precise geroscience." This represents a key objective of the UConn Pepper Center, which is overseen by the study’s co-authors George Kuchel, MD, and Richard Fortinsky, PhD.

In order to conduct this comprehensive study, Diniz collaborated with colleagues from various departments at UConn and UConn Health, such as Kuchel; Fortinsky; Zhiduo Chen, Ph.D.; David C. Steffens, MD; and Chia-Ling Kuo, Ph.D. Additionally, the research group consisted of experts from the University of Exeter in the UK and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health located in Toronto, Canada.

Depression's 'silent consequences'

This study highlights the deep relationship between the mind and body, particularly focusing on the lasting effects of unaddressed psychological disorders. For individuals not involved in science, Diniz aims for this research to encourage greater attention to mental well-being comparable to how we view physical health.

Seeking assistance is crucial," Diniz emphasizes. "It isn’t just necessary when you’re 50 or beyond—every stage of life matters. Numerous research findings from the last ten years indicate that any instance of depression during one’s lifetime, including in your twenties, may elevate the likelihood of developing dementia eventually. Therefore, seeking support is vital, as is addressing the condition and striving for complete recovery from the depressive episode.

Luckily, he points out, numerous lifestyle suggestions that have proven effective in alleviating depressive symptoms—such as physical activity and avoiding tobacco use—also enhance overall well-being, meaning that addressing depression doesn’t have to be done separately from general health care.

Providing patients and healthcare professionals with resources such as the Proteomic Risk Score and a broader perspective on wellness, this study contributes to an expanding collection of work focused on stopping numerous instances of ADRD at an earlier stage.

More information: Breno Satler Diniz and colleagues, Proteogenomic profile of Alzheimer's disease and associated dementia risk in people suffering from major depression Nature Mental Health (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-025-00460-0

Supplied by the University of Connecticut

This narrative first appeared on Medical Xpress .

Posting Komentar untuk "Decoding the Connection: Depression and Alzheimer's Explained"

Please Leave a wise comment, Thank you